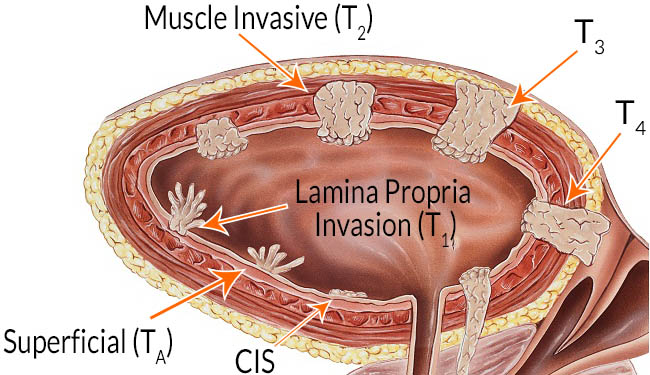

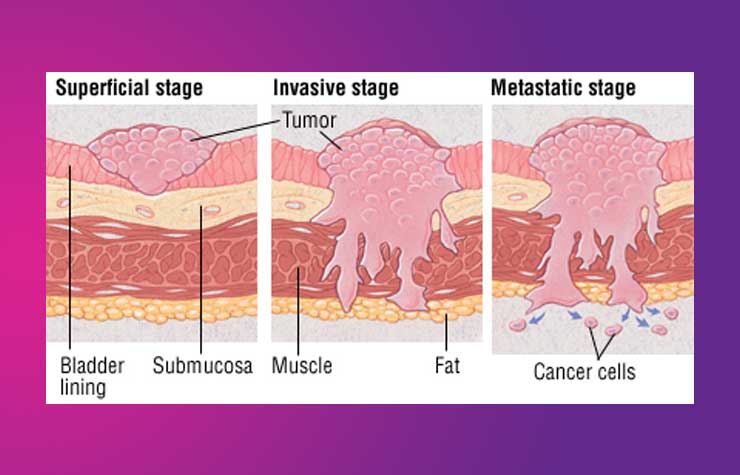

Although T1 cancers are in the NMIBC group, they can be quite aggressive, especially if they are of a higher grade. Grade relates to the biological aggression of cancer, and again,is provided by the pathologist. Higher the grade worse is the outlook.

How is NMIBC managed?

Following TURBT, a chemotherapeutic agent called mitomycin is usually left within the bladder (intravesical chemotherapy) for an hour or so either on the same day or the following day. This reduces the recurrence rate of cancer within the bladder. This does not have any systemic side effects like balding, nausea, vomiting, etc.

Tis/ Cis – tumour in situ or carcinoma in situ – this is pre-cancerous change in the mucosa (the inner lining of the bladder). In bladder, presence of Cis means aggressive disease, and is therefore managed aggressively. Cis can present alone or along with Ta/T1/T2 disease.

Cis is usually managed by way of immunotherapy using BCG vaccine (the same vaccine that is used in the prevention of tuberculosis) that is instilled at regular intervals within the bladder. The vaccine is left inside the bladder for 1-2 hours during each session and then emptied. The bladder is inspected a few weeks following this to see if there is any remaining disease. The immune reaction caused by the BCG kills the precancerous cells. Your urologist will discuss the regime of intravesical BCG therapy that is appropriate for your situation. The side effects of BCG will be discussed in detail with you as well.

In those who do not tolerate BCG well, alternativeslike mitomycin or doxorubicin may be used.

Ta – these tumours involve only the mucosa. These can usually be cured but they have a tendency to recur. If they occur too frequently, or in several areas of the bladder and is difficult to control with TURBT or fulguration of the tumour (your urologist may call this cystodiathermy), your urologist may decide to treat this with regular intravesical chemotherapy. In the more aggressive cases it may have to be managed like IBC.

T1 – most of these are managed similar to Ta, but since they are more aggressive, they are likely to be treated with intravesical BCG therapy as well (similar to Cis). If there is more than one T1 tumour or if there is recurrence of T1 disease, your urologist is likely to consider managing this like IBC.

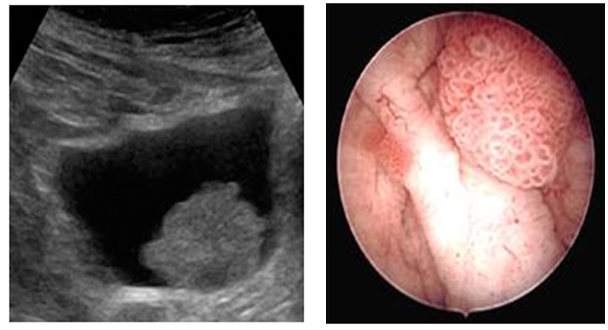

If NMIBC is managed endoscopically (which is the case in the majority of them), your urologist will advise repeat checks of your bladder (referred to as check cystoscopy) at regular intervals. This allows early detection and treatment of any recurrent cancer.

How is IBC managed?

The management of IBC is highly individualized and depends on several factors – age, general health and fitness, presence of metastasis (spread of cancer to other organs), etc. In general terms, it is useful to discuss the aim of treatment with your urologist:

Cure the cancer: although this is realistically achievable, in some cases they can recur a few months or years later. Hence, doctors tend to use the word remission rather than cure. This merely implies lack of any sign to indicate presence of cancer following treatment but may or may not represent cure.

Control the cancer: cure may not be possible in some instances but treatment is likely to provide long-term symptom control and therefore a better quality of life.

Ease symptoms (palliation): if cure is not possible then other treatments to control the growth of cancer can reduce bleeding and pain. In advanced cancer, pain relief and other treatments for symptom relief may be required.

Surgery

The most common operation is removal of the bladder – cystectomy. Please see BLADDER SURGERY – pt guide for details.

Radiotherapy

This uses high-energy beams of radiation that are targeted on the bladder to treat the cancerous tissue and is sometimes used instead of surgery. This is usually delivered in ‘fractions’ over several weeks and your radiation oncologist will discuss this in detail with you.

Chemotherapy

Cancer busting drugs may be given over a period of a few weeks prior to surgery or radiotherapy – this is termed neoadjuvant chemotherapy – to increase the chance of cure. If given after surgery it is called adjuvant chemotherapy.

It is quite likely that you will be managed by a team of professionals including medical / radiation oncologists, stoma therapists, specialists in pain relief, specialist nurses, etc. Your urologist is the best person to advise you on the management and prognosis (outlook) based on your specific circumstances.