What is pelvi-ureteric junction?

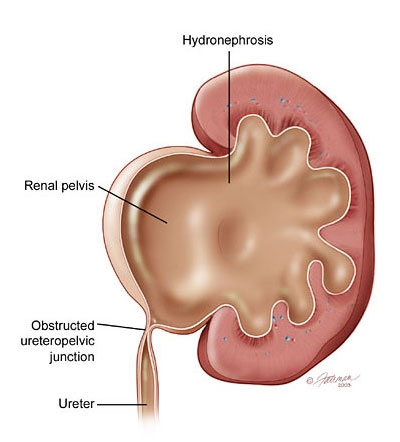

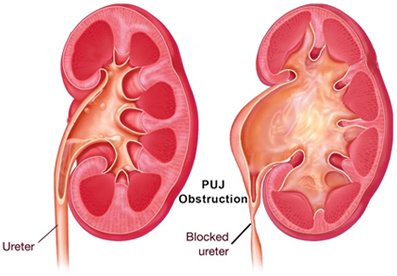

Urine that is formed in the kidney collects in a funnel shaped part called the pelvis of the kidney (renal pelvis) from where it is actively propelled down the ureter to the bladder. The junction between the pelvis of the kidney and the ureter is referred to as the pelvi-ureteric junction (Americans tend to refer to this as the uretero-pelvic junction – UPJ).

What is PUJO?

The junction between the renal pelvis and ureter is narrow which then blocks the passage of urine. In time the pelvis and later the calyces become larger (hydronephrosis) and urine stays longer here. If this continues, the pressure in the pelvis can start affecting the function of the kidney. In time, the whole kidney becomes baggy and non-functional.

What causes PUJO?

Most of those with PUJO are likely to have been born with this condition (congenital PUJO). This occurs approximately in 1 in 1500 children. With ultrasound screening of pregnancies now becoming routine, most are picked up prior to childbirth.

The figure on the right shows a case of severe hydronephrosis of the left kidney noted on ultrasound at 32 weeks of pregnancy. It is to be noted that not all cases of hydronephrosis in the baby’s (fetal) kidneys picked up during pregnancy end up being PUJO. Most cases of mild hydronephrosis resolve when followed up with repeat ultrasound scans of the baby.

On the other hand, the majority of those with moderate to severe hydronephrosis are likely to require intervention at some point. It is best for all cases of antenatally detected hydronephrosis to be followed up by a qualified paediatrician (child specialist). Figure on the right shows ultrasound picture of hydronephrosesof both kidneys in a fetus. Congenital PUJO if undetected in childhood may manifest in later life or remain ‘silent’ through out life. PUJO can also be caused by stones, tumours, previous surgery or inflammatory conditions of the kidney / ureter.