Where are the kidneys and what do they do?

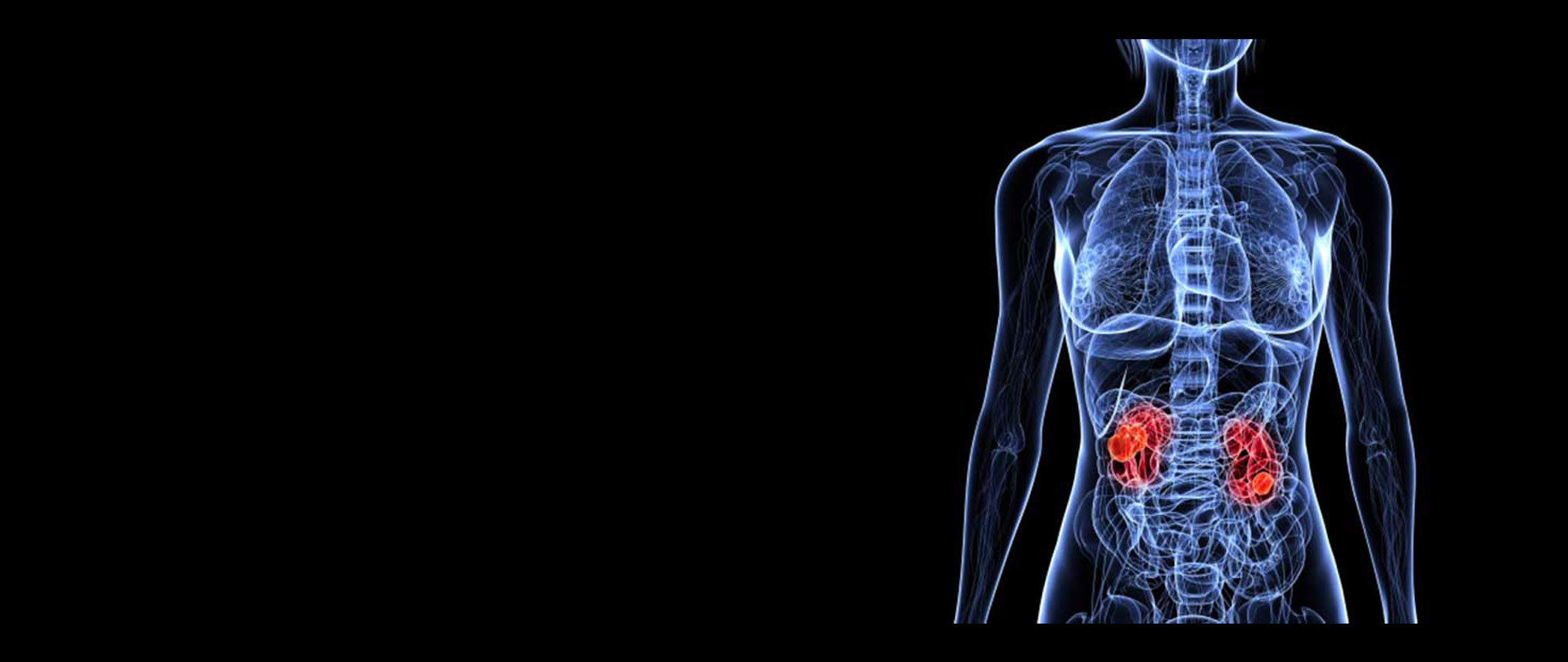

Everyone has two kidneys, one on either side of the spine, located in the back of the abdomen, behind the intestines. The kidneys are bean shaped and are about the size of a large mango.

A large artery (the renal artery) supplies blood to each kidney, which is then filtered through special structures called nephrons. The filtrate passes through special tubes (called tubules and collecting ducts) as urine, which eventually drains, into the calyces and renal pelvis. This is then propelled actively down the ureter to the bladder. Whilst waste material is expelled in the urine, other components are returned to the blood via veins, which eventually drain into the renal vein and returned back to the circulation.

In addition to its filtering function, the kidney is involved in the production of a few hormones:

Renin – helps regulate blood pressure.

Erythropoietin – helps stimulate the bone marrow in the production of red blood cells.

Calcitriol – helps regulate calcium level in the blood.